Jacob Eyferth, University of Chicago

Summary

Throughout the collective period, millions of rural Chinese continued to wear handloom cloth, and rural women continued to spend much of their working hours spinning, weaving, and making cloth and clothing. In theory, manual spinning and weaving should have ended after 1949, since every Chinese citizen had access to factory cloth through the rationing system. In actual fact, rural rations fell short of replacement needs, and women worked double shifts to clothe their families. Women’s unrecognized domestic work enabled the state to undersupply the countryside and direct scarce resources to the cities.Introduction

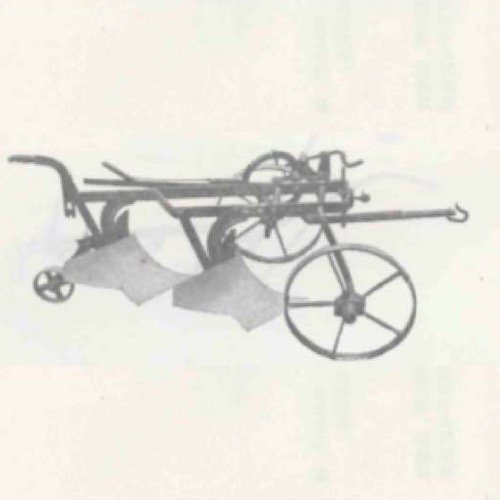

Inconspicuous as it is, this bolt of handloom cloth stands for the domestic work of rural women and for their invisible and unrewarded contribution to China’s economic development [see ⧉source: Handloom cloth from Zhouzhi, also depicted to the left]. It is 14.40 m long, 48 cm wide, and weighs 1.560 kg. The pattern is a plain weave (a simple crisscross pattern: each weft yarn goes over one warp yarn, then under the next, then over again) with 35 warp threads and 35 weft threads per inch. The cloth was woven on a wooden handloom similar to the one depicted in this image [see ⧉source: Handloom cloth production, Image 1]. The yarn is hand-spun, and its evenness suggests that it was made by an expert spinner. It was however spun from poor cotton: the fibers are short, the thread discolored, and it contains fragments of bolls and seeds that broke during ginning. This is coarse, thick, heavy cloth, scratchy to wear at first but warm and comfortable once broken in. I bought it in December 2006 in the village of Gedatou, Zhouzhi County, in the central part of Shaanxi known as Guanzhong ('between the passes'), from a widow in her sixties named Gao Fenglan. Gao was no longer sure when she wove this particular piece but it must have been in the late Mao or early post-Mao years, when cotton was easily available and many women still spun and wove. She intended it for her daughters’ dowries, but in the 1980s, when her daughters married, textiles from urban factories were widely available and handloom cloth was no longer considered an appropriate dowry item. Like many other village women, Gao kept her handloom cloth in a chest, even though she knew that no one would ever wear it.

Cloth of this type is locally known as baibu (白布 'white cloth,' as opposed to striped or checkered cloth). The generic name for handloom cloth is tubu (土布): 'local' or 'rural' cloth, as opposed to textiles made on power looms in urban factories. Tubu was traditionally worn undyed, or it dyed dark blue with indigo. Synthetic dyes, which made it possible to weave complex stripes and checkers, reached the area only the 1970s. Striped and checkered cloth was used mostly for the lining of thick quilts and padded winter clothes [see ⧉source: Handloom cloth production], while the outside of such clothes was typically dyed black or blue.

Clothing needs and labor time

In Chinese units of measurement, the bolt depicted here is 1.4 chi (尺) wide and 4.3 zhang (丈) long.1 Depending on the cut, it takes 1.5 to 1.7 zhang to make a suit of clothes, i.e. one shirt or jacket and one pair of trousers. Our three-zhang bolt is thus just enough to make two unlined summer suits or a lined suit for a short adult. Minimum clothing needs are difficult to determine: in the harsh climate of North China, absence of body cover kills just as surely as an absence of food, but how much cloth a person needs over the course of a year depends on a variety of factors. Based on interviews, I estimate that a farmer who worked outdoors in all seasons needed a minimum of two unlined summer suits, worn and washed in turn, and a lined suit for the spring and autumn season. This lined suit can be turned into a padded winter suit by taking it apart and inserting a layer of cotton wool. In addition, one needs one pair of padded cloth shoes (in summer, most people went barefoot or wore straw shoes), socks or foot wrappers, a headscarf for protection from the summer sun, and a few other items.2 Underwear was not required and indeed not much used. Bedding was shared between family members and lasted several years, so that yearly per capita consumption was quite low. I estimate a total yearly need for an adult person of 13.33 m, or an average minimum, adjusted for the lower needs of children, of 9.33 m. This is a physical minimum, in the sense that a person with less cloth is unable to fully participate in outdoors production work. Social minima are higher: the average person would need 12 to 14 m to meet customary norms of cleanliness and decency.

Our bolt here, then, falls just short of an adult’s yearly needs. It represents a substantial time investment: a practiced spinner who worked from dusk to dawn would take three days to spin a jin 斤 (500 g) of thread. However, most spinning was done by girls, who might need about five days for the same amount. With a weight of a bit more than three jin, the bolt thus incorporates 15 days of girls’ work. Weaving itself is fast, but if we include the time for starching and spooling the yarn and setting up the loom, we arrive at two labor days per zhang of cloth, or 6 days for the bolt. Total labor time for the bolt – excluding preparatory work such as ginning and carding – thus amounts to 21 days. Three weeks of work, then, suffice to provide for most of the yearly textile needs of an adult person. This does not yet include the time for making and mending clothes or for making cloth shoes. A 1954 article in the People’s Daily – one of very few articles from the Mao years that comment explicitly on rural textile work – estimates that a woman who was the sole provider for a family of four would have to spend six month each year meet her family’s needs [see ⧉source: People's Daily article].3 Gao Fenglan produced all the cloth and clothing for a family of 11 consisting of herself, her husband, her mother-in-law, four sons, and four daughters; in addition, she also made all the cloth and clothing for her parents. Her daughters would have helped with spinning from an early age (most girls learned to spin when they turned seven), but unlike Gao herself, who never went to school, her daughters spent most of their childhood years in school. Women like Gao spent almost all of their entire waking hours at the spinning wheel or the loom.

The place of handloom cloth in the political economy of Mao-era China

The most interesting fact about this bolt is that it should not exist at all. When the Communist Party came to power, it planned to phase out wasteful, time-consuming, inefficient handloom weaving. All cotton was to be sold to the state, to be processed in state-owned factories and be sold back to consumers, or exported abroad, at a profit. After 1954, all private trade in cotton and cotton goods was banned, and cotton farmers were required to sell their entire harvest, apart from a one-kg allowance for domestic use, to the state. At the same time, a rationing system ensured that every Chinese citizen had access to inexpensive textiles from state-owned cotton mills. In theory, then, hand spinning and hand weaving should have come to an end, as rural women had neither the need nor the means to produce cloth at home. However, this is not how things worked out. The cotton monopoly became one of the motors of socialist industrialization: since the state controlled prices at both ends, it could ensure high profit rates for textile factories. Mills built in the 1950s earned back their investment within a single year, and profits from the cotton industry paid for much needed imports from the Soviet Union. However, China had never produced much of a cotton surplus: in 1929, China’s per capita consumption of cotton cloth was one of the lowest in the world, lower than India’s and barely above Sudan. With exports rising to 23 percent of output in the early 1960s, and with growing urban demand, China simply did not produce enough factory cloth to provide for all needs, and rural needs were sacrificed to those of the urban and export market [see ⧉source: rural and urban cloth consumption from 1952 to 1982]. Rural cloth rations were typically one-half of urban rations; nationwide, they fluctuated between 8.76 m (1959) and 2.32 m (1961), with a long-term rural average for the years 1952 to 1978 of 5.53 m. Factory cloth was slightly wider, and the heavy twills produced since the mid-1960s were more durable than handloom cloth. Nonetheless, even the highest rural rations fell far short of long-term replacement needs. A person who relied entirely on rations, without additional supplies, would have reached the end of the collective period with clothes not only patched (as was the norm in both rural and urban China) but in rags. In fact, most people I interviewed did not even use their ration coupons: coupons entitled their holder to purchase a given quantity of cloth, but the cloth still had to be paid. For rural people whose cash income was typically in the range of 10-20 yuan per year, even the cheapest factory cloth was unaffordable. People therefore sold their ration coupons on the black market and wore tubu cloth instead.

The Chinese state, in short, undersupplied the rural population for 25 years, tacitly assuming that rural women would find ways to fill the gap. This they did, in ways that brought them into latent conflict with the state. As mentioned above, collective farms were supposed to sell their entire cotton harvest to the state, retaining only one kg of ginned cotton per capita. This was meant for padding quilts and winter clothes, not for spinning, but many women span their cotton allowance into thread instead. Collectives also hid part of their harvest from the state and distributed it to their members. They also allowed cotton to spoil on the field by leaving it out in the winter rain, and then distributed the spoiled stalks to households as fuel. People then dried the stalks at home and removed the remaining cotton from the bolls. Such cotton was short-fibered and difficult to process, but an experienced spinner could still turn it into yarn. Finally, people stole from the collective cotton field, with or without the connivance of team leaders.

Labor time, like cotton, belonged to the collective: as a common slogan had it, the needs of the state came first, followed by those of the collective, with individuals coming last (xian guojia, hou jiti, zai geren 先国家,后集体,再个人). All adult, able-bodied women were expected to participate in collective work, although they could skip a shift to take care of urgent household needs. Before collectivization, women in North China worked at home, participating in farm work mostly during the busy seasons. In Zhouzhi, the average rural woman worked only ten days a year in agriculture; after collectivization, this number shot up to 200 days. Women thus shouldered the double burden of working full-time in the field while doing household chores and raising more children than any generation before or after them. Textile work took place in stolen moments between shifts, or late at night after men and children had gone to bed. The women I interviewed remembered the collective years as a time of overwork and sleep deprivation. They also remembered it as a time of conflicting obligations: their families expected them to provide food and clothing, but they also needed to earn work points in collective work. Time spent at the spinning wheel or the loom [see ⧉source: Line drawing of a handloom] was time not spent in the fields; more warmth and comfort on the skin meant fewer work points and thus reduced cash and grain incomes. While unrewarded and unrecognized, this tedious, time-consuming work underpinned capital accumulation and industrialization in the Mao years.

Footnotes

10 chi =1 zhang = 3.33 m.

One way to stretch resources further was to take apart the winter suit in spring, remove the padding, wash the pieces, and reconstitute shell and lining as two separate suits, to be put back together as a padded suit when the weather turned cold again. This practice was common in poor mountain areas but not in Guanzhong.

'How does the Ma Tinghai Agricultural Production Cooperative mobilize women to participate in production' (Ma Tinghai nongye shengchan hezuoshe shi zenyang fadong funü canjia shengchan de 马廷海农业生产合作社是怎样发动妇女参加农业生产的), Renmin Ribao, 2 February 1954, 2.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

Further Reading

Chao, Kang (Gang Zhao). The Development of Cotton Textile Production in China. Cambridge: East Asian Research Center, 1977.

Eyferth, Jacob. 'Liberation from the Loom? Rural Women, Textile Work and Revolution in North China'. In Maoism at the Grassroots: Everyday Life in China’s Era of High Socialism, edited by Jeremy Brown and Matthew D. Johnson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Hershatter, Gail. The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Jacka, Tamara. Women’s Work in Rural China: Change and Continuity in an Era of Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.